Article by Lalita Panicker, Consulting Editor, Views and Editor, Insight, Hindustan Times, New Delhi

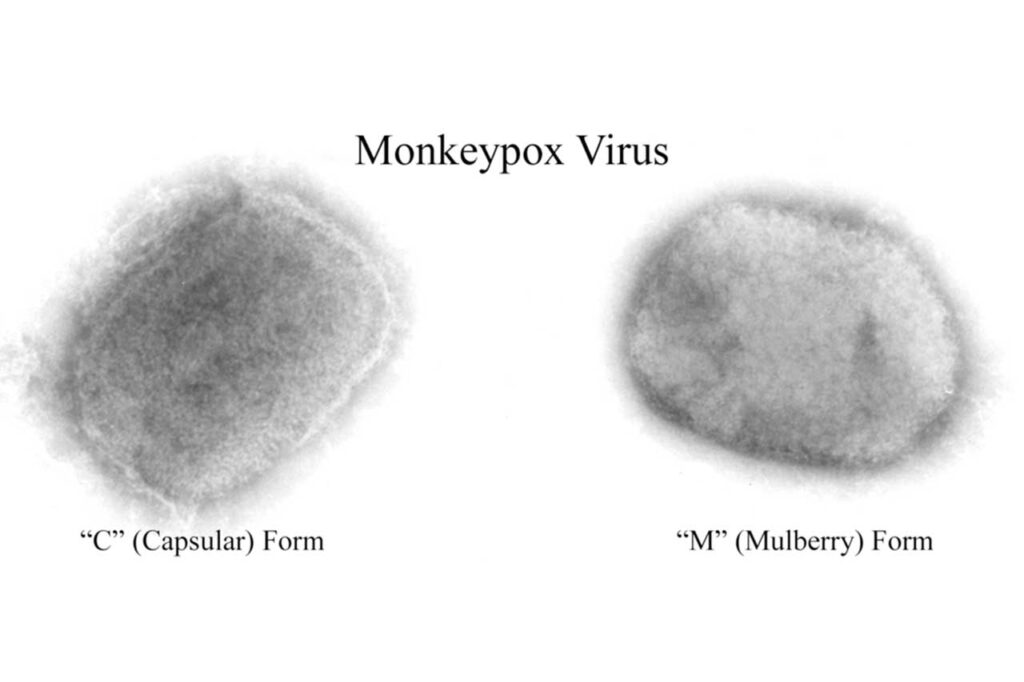

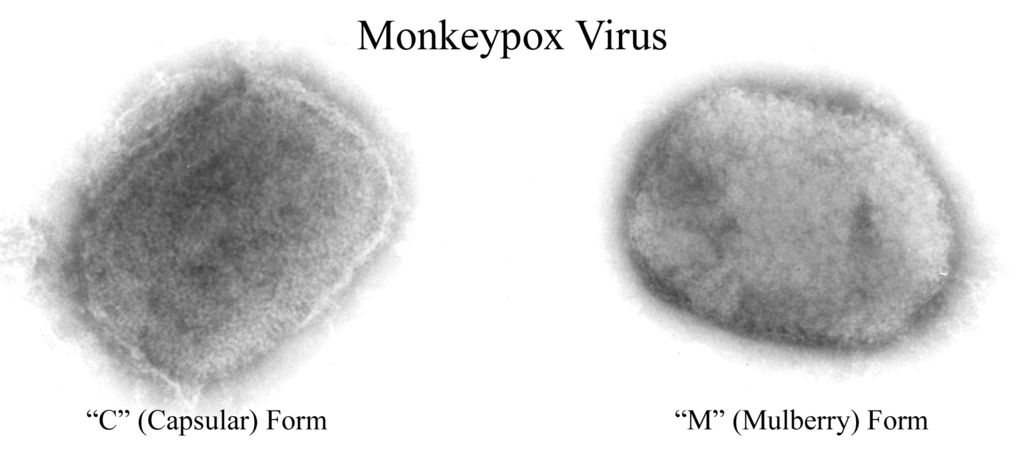

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared mpox a public health emergency of international concern. Cases of mpox — previously called monkeypox — have been surging in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In recent weeks, cases have appeared in nearby African countries, including several that have never reported mpox cases before. www.npr.org/sections/goats-and-soda/2024/08/14/g-s1-16977/mpox-public-health-emergency-world-health-organization-who?

“What we’re seeing is the tip of the iceberg” because of weaknesses in the surveillance system, says Dr Dimie Ogoina, the chair of the emergency committee convened by WHO and an infectious disease physician at Niger Delta University in Nigeria.

WHO has declared seven public health emergencies in the past, including one for mpox in 2022. The type of mpox that is circulating now is known to be more deadly than the type that swept the globe two years ago.

A day earlier, the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) took a similar step, declaring mpox an emergency.

Africa CDC has never done anything like this before.

“We can no longer be reactive — we need to be proactive and aggressive,” says Dr Jean Kaseya, director-general of Africa CDC. “This is a fight for all Africans and we will fight it together.”

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), children make up the majority of the 14,000 reported cases and 511 deaths so far in 2024. Those numbers roughly match the number of cases reported in all of last year in the country — and they dwarf the mpox numbers reported in 2022.

In the last couple of weeks, there has been a new and alarming development. Mpox has been detected in countries that have never previously identified cases. About 50 confirmed cases and more suspected cases have been reported in Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda, according to WHO officials.

It is with past health emergencies in mind that Africa CDC is trying to move quickly and garner international support. “We were abandoned during COVID time, and today we don’t want to be again abandoned. We don’t want to be dependent. We are taking appropriate action,” says Kaseya, noting that declaring a public health emergency is a new power that the African Union gave to the agency in 2023. Kaseya says that the agency sought input from more than 600 experts and that the scientific committee that was convened to consider the mpox situation unanimously recommended the emergency declaration.

Kaseya says it’s particularly concerning that about 70% of cases in the DRC are in children under 18. “This one is a major alarm for the world,” he says. “We are losing the youth in Africa.”

Experts say the higher number of cases and deaths among children is likely because they don’t have protection from the smallpox vaccine — which was discontinued after that related virus was eliminated in 1980 — and because about 40% of children in the region are malnourished, making it harder for their bodies to fight off the virus.

There’s concern about mpox in the U.S. as well. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an mpox alert last week. While the risk to the general population in the U.S. remains low, Christina Hutson, senior science adviser at the U.S. CDC, says it’s important for clinicians, health departments and travellers to be aware of the virus’s spread in Africa and be vigilant about symptoms.

In addition, last week the U.S. pledged nearly $424 million to help with what the U.S. Agency for International Development calls an “ongoing catastrophe” in the DRC, plus $10 million to respond to mpox and 50,000 mpox vaccine doses.

While Japan, the U.S., the European Union and vaccine manufacturers are working on vaccine donations, Africa CDC says the need far outstrips what’s in the pipeline.

“We need to have vaccines. Today, we are just talking about almost 200,000 doses [becoming] available. We need at least 10 million doses,” says Kaseya. “The vaccine is so expensive — we can put it around $100 per dose. There are not so many countries in Africa that can afford the cost of this vaccine.”

The mere announcement that WHO was convening an emergency committee today had already spurred some action, says Alexandra Phelan, a global health law expert at Johns Hopkins University, pointing to a decision by the European Union today to donate 215,000 doses of mpox vaccine to Africa CDC. “While that is a drop in the ocean of the 10 million vaccines the Africa CDC says are needed, it shows that this process serves as an important alert to the international community,” Phelan says.

But outbreaks have steadily grown in size, and two recent, separate developments have raised alarm.

The type of mpox spreading in the DRC’s east — particularly among sex workers and other adults — and into some of the neighbouring countries is a subtype called clade Ib. (Clade is the term used for mpox variants.) This is a new type of mpox that has kept scientists on their toes, discovering new information that is both good and bad.

It’s harder for diagnostic tests to pick it up because of a genetic change in the virus, says Hutson of the U.S. CDC. It’s also the first time clade Ib has been spread through sexual transmission. However, it also seems less fatal than the original clade I circulating elsewhere in the DRC. The number of people who have died has dropped below 1%. At least that, she says, is a glimmer of good news.

////

In 2023, more than 47,000 people died from heat in 35 countries in Europe, scientists estimate this week in Nature Medicine. It was the second highest number from 2015 to 2023, surpassed only in 2022, they say. The rise in Europe underscores an EU finding this year that the continent is the fastest-warming; 2020 and 2023 were Europe’s warmest 2 years on record. Deaths attributed to heat waves are prompting new calls for preventive actions. In July, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres urged nations to care for vulnerable people, protect outdoor workers, and intensify efforts to curb emissions of greenhouse gases, which are contributing to more frequent and severe heat waves. www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-europe-s-heat-related-deaths-antarctic-vegetation-and-stonehenge-s-faraway?

////

For the first time in nearly 40 years, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) last week issued an emergency ban on sales and use of a pesticide, citing an imminent health hazard. www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-europe-s-heat-related-deaths-antarctic-vegetation-and-stonehenge-s-faraway?

The chemical, dimethyl tetra chloroterephthalate (DCPA), marketed under the trade name Dacthal, has been used in California, Wisconsin, and Washington state to control weeds that compete with broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and related crops for water and sunlight. The weedkiller could disrupt thyroid hormones in human foetuses, harming brain development and causing other health effects, according to recent studies. The agency cited risks of exposure to pregnant workers who apply the weedkiller or enter treated fields. Bystanders could also be exposed. Growers can switch to alternative herbicides for some crops but not others, such as bok choy and kale; these growers might lose up to 20% of revenue, EPA estimates.

////

After a 2013 outbreak of avian influenza in China killed about 35% of the people it infected, immunologist Katherine Kedzierska of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity set out to answer a baffling question: Why did some patients die while others survived?

This week in Cell, Kedzierska and colleagues at 16 other institutes around the world provide a possible answer. The sickest people, it turns out, produced significantly higher levels of an enzyme called oleoyl-acyl-carrier-protein hydrolase (OLAH), which is involved in the production of oleic acid, a fatty substance critical to human health that is found in our cell membranes. Before this study, “nothing was known that linked it to infectious diseases,” Kedzierska says. www.science.org/content/article/unexpected-gene-may-help-determine-whether-you-survive-flu-or-covid-19?

OLAH appears to determine the odds of succumbing to several other viral respiratory diseases as well, including COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). The researchers hope the finding can help identify patients at high risk of severe complications early in the disease course, and they are hunting for treatments that can bring down OLAH levels.

“This is a very nice study,” says Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a virologist at the of the University of Wisconsin-Madison who specializes in influenza. It reflects a tremendous amount of work, adds virologist Richard Webby, an influenza researcher at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. But he stresses that several factors likely contribute to a person developing severe influenza. “The one thing I can never wrap my head around with such studies is how big of an impact these molecules have on their own,” he says.

The researchers started by analysing blood samples taken from four people who died from H7N9 influenza, which ravaged Chinese poultry and first jumped to humans in 2013, leading to the largest bird flu outbreak in people to date. They compared these samples with blood from four people who survived the infection. “We embarked on this study to really understand what immune responses drove recovery,” Kedzierska explains.

As expected, the fatal cases had higher levels of inflammation driven by a “cytokine storm,” a surge of messenger molecules that direct immune cells to respond to infections. But when they analysed gene expression—the levels of messenger RNA (mRNA), which codes for proteins—shortly after the patients were admitted to the hospital, they found that 10 genes were expressed at either higher or lower levels in the sicker patients. OLAH stood out: Its expression level was about 82 times higher.

The team then found that three seasonal influenza patients on ventilators at U.S. hospitals had far higher OLAH mRNA levels than two healthy controls. And OLAH expression levels were also elevated in the most severely ill group in a cohort of 143 COVID-19 patients at U.S. paediatric hospitals. Finally, analysing blood from 23 children in a Memphis, Tennessee, hospital revealed a correlation between high OLAH levels and severe disease from RSV.

Several factors determine how ill people become from infections with respiratory viruses, including other health conditions they may have, their innate immune responses, and immunity from previous infections. To better understand the role of OLAH, the researchers engineered mice to cripple the OLAH gene and inoculated them with levels of an influenza virus high enough to kill them.

The virus killed fewer than 7% of these knock-out animals, compared with 50% of control mice with intact OLAH genes. “I think what we managed to identify here is something quite major,” says immunologist Brendon Chua, who co-led the studies. “It’s sort of the gatekeeper that kickstarts the [inflammation] process.”

Seeking to explain how OLAH might cause harm, the researchers found that high levels of the enzyme prompted an increase in lipid droplets in the blood that, in turn, led to damaging levels of inflammation-causing cytokines. OLAH also helps viruses copy themselves.

Why some people have such high OLAH expression levels remains unclear.

Although oleic acid is found in high levels in many foods, especially olive oil, it’s unlikely that reducing consumption would lower our risk of a severe respiratory infection, Kedzierska stresses, because the amount we ingest pales in comparison to the amount our bodies naturally make.

Chua is now trying to find compounds that inhibit OLAH and might be used as a therapeutic for patients who show up with respiratory infections and high levels of oleic acid. The team also hopes to develop a diagnostic test that can measure levels of the enzyme and, ultimately, predict disease severity. “When patients are admitted to the hospital, it’s really hard to know which patients will survive and which patients will die,” Kedzierska says.