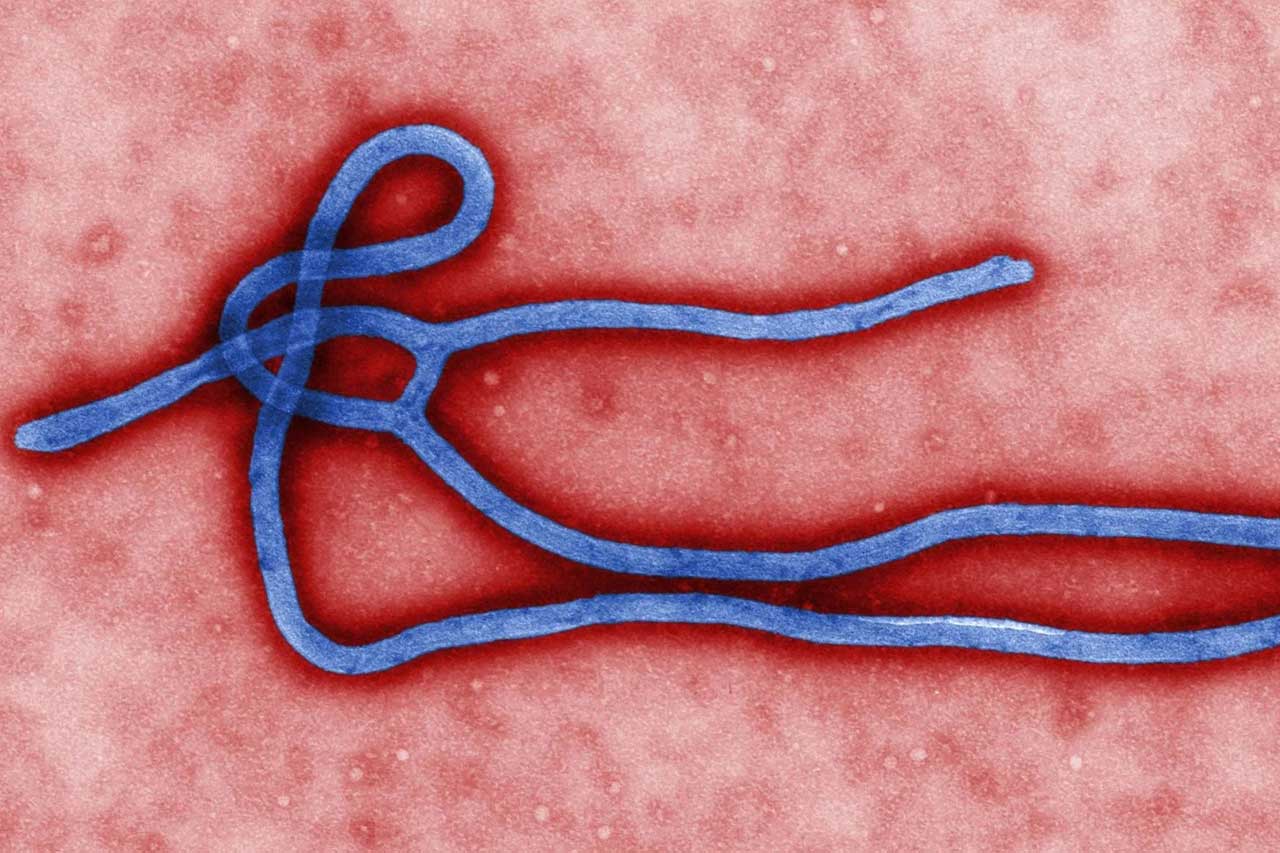

A multipronged international effort has begun to launch trials of experimental Ebola vaccines in Uganda, which declared an outbreak of the deadly disease on 20 September. According to the most recent WHO update, Uganda has had 18 confirmed and 18 suspected cases of Ebola, including 23 deaths—an unusually high case fatality rate of 64%. A trial of a vaccine candidate that’s farthest along in development could launch before the end of next month. www.science.org/content/article/scientists-race-test-vaccines-uganda-s-ebola-outbreak?

Proven vaccines exist for Zaire ebolavirus, which has led to a dozen outbreaks in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and was responsible for the massive Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014. But those vaccines cannot control this outbreak because it’s being driven by a distant viral relative known as Sudan ebolavirus, which last caused an outbreak, also in Uganda, in 2012. The Zaire and Sudan ebolaviruses “are not variants and they’re not strains—they’re different viruses,” says Nancy Sullivan, who heads biodefense research at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and has collaborated on Ebola vaccine studies. Researchers have long recognized that the world badly needs a Sudan ebolavirus vaccine: In 2016, Science published a survey of 50 leading vaccine researchers who ranked the Sudan ebolavirus vaccine as the number one R&D priority based on feasibility and need. But vaccine makers have had little financial incentive to produce one. Even if the current trial succeeds, producing enough doses fast enough will be a challenge.

Three experimental Sudan ebolavirus vaccines have been tested in human studies, but because outbreaks are so rare, they have not had a real-world test. “We are moving really fast this time and people are really willing to work to get these vaccines on the ground,” says Ana Maria Henao-Restrepo, a WHO vaccine specialist who is coordinating discussions between the Ugandan government and stakeholders elsewhere in the world, including vaccine manufacturers, funders, and non-governmental organizations.

The farthest ahead is a candidate that the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline began to develop during the West African outbreak; GSK donated the license for it to the non-profit Sabin Vaccine Institute in 2019. The single-dose vaccine contains the gene for the surface protein of the virus stitched into a harmless chimpanzee adenovirus (ChAd), which serves as a shuttle to deliver the payload into cells. The U.S. government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority in 2019 awarded Sabin a $128 million contract to develop the product, and the candidate has worked well in monkey studies and small-scale clinical trials conducted by NIAID’s Vaccine Research Centre.

Henao-Restrepo says WHO organized two rounds of consultations this week with vaccine developers and others, which led to a unanimous agreement that the Sabin candidate should be first in line for a Ugandan trial. Ugandan health officials are now evaluating a draft proposal for this trial. If all goes well, Henao-Restrepo says a study could begin before the end of October.