Article by Lalita Panicker, Consulting Editor, Views and Editor, Insight, Hindustan Times, New Delhi

A panel advising the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last week recommended that it approve a vaccine given to pregnant people to protect infants from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which can cause severe lung infections. https://www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-china-s-ethics-oversight-arpa-h-s-new-science-and-210-million-protein?

The vote was unanimous based on the efficacy of the vaccine, called RSVpreF and branded Abrysvo. Ten members of the panel also endorsed the safety of the vaccine, which is designed to cause mothers to produce protective antibodies that their babies acquire during pregnancy. But four panel members weren’t persuaded. A large, phase 3 trial by Pfizer, maker of the shot, found an elevated rate of premature births—5.7% in the vaccinated group versus 4.7% in the placebo group—but the difference did not reach statistical significance and neonatal deaths did not increase. Lower respiratory tract infections from RSV kill an estimated 46,000 babies younger than 7 months every year, hundreds of them in the United States, where RSV is the leading cause of infant hospitalization. The Pfizer vaccine was 69.4% efficacious in protecting this age group from severe disease. FDA is expected to rule in August whether to license the vaccine.

////

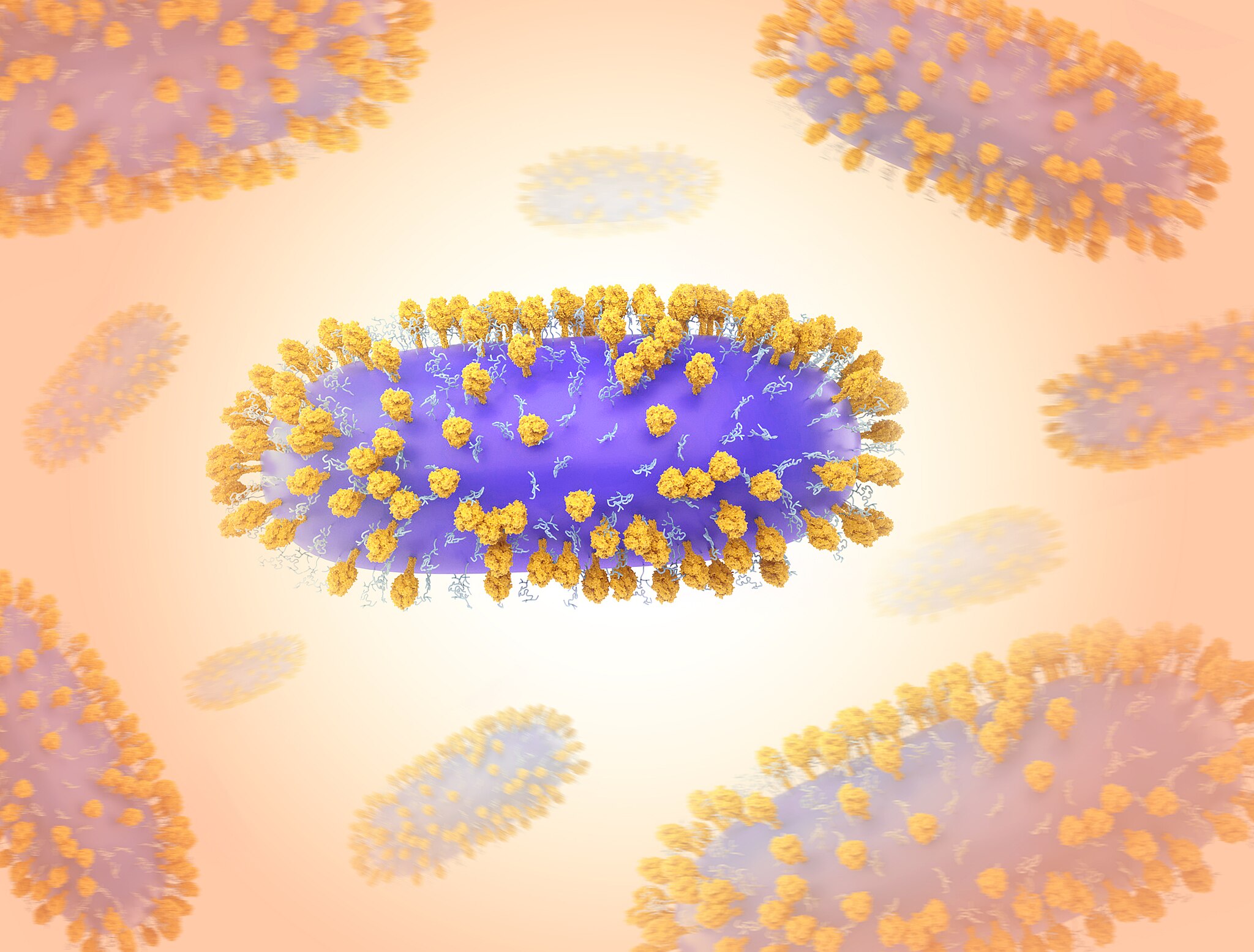

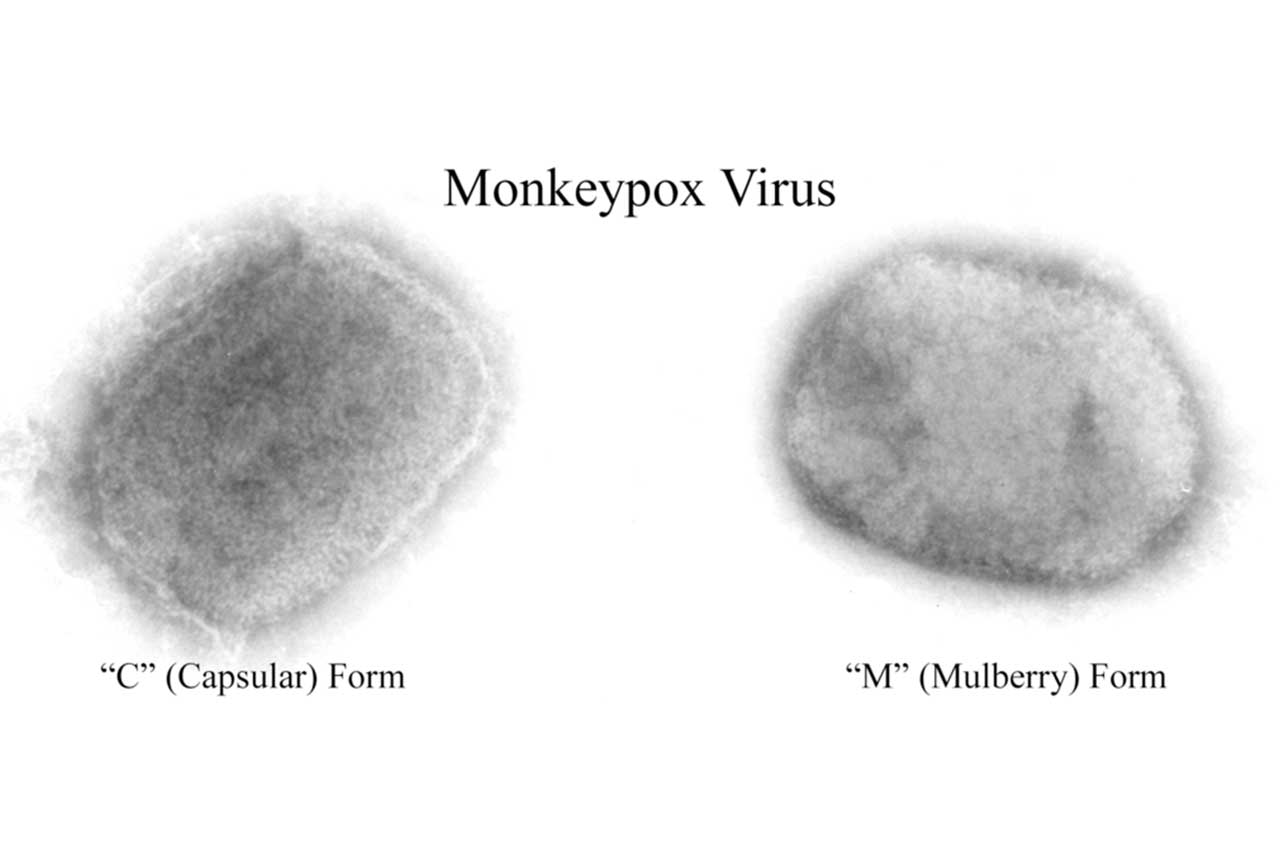

A year after many countries started to immunize those at highest risk of mpox during a global outbreak, a study has shown the shots are effective against the monkeypox virus. The vaccine, called Jynneos and manufactured by Bavarian Nordic, was originally developed as a smallpox vaccine and licensed for mpox based largely on animal data. Now, researchers have used U.S. electronic health records to compare 2193 patients diagnosed with mpox with 8319 matched controls who were considered at high risk because they were living with HIV or taking pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection. (Mpox has primarily spread among men who have sex with men and their sexual networks.) Those in the control group were much more likely to have received the vaccine, the researchers report in The New England Journal of Medicine. They estimate it was 66% effective for those who received a full course of two doses and 35.8% for those who received only a single dose.

////

The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) this month warned it will crack down on researchers over ethics violations, highlighting a case involving human embryonic development. www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-china-s-ethics-oversight-arpa-h-s-new-science-and-210-million-protein?

A CAS ethics official told the academy’s China Science Daily newspaper that investigators concluded researchers falsified an ethics review report for a study that produced cells resembling human embryonic stem cells in vitro and implanted chimeric embryos containing both human and mouse cells into female mice. CAS reduced the unidentified team leader’s funding and suspended him

from supervising postgraduates for a year, according to the news report. In an email to Science, Miguel Esteban, a stem cell biologist at CAS’s Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health, acknowledges he led the research in question, which he and colleagues published in Nature in March 2022. He denies falsifying documents and says the team followed international regulations and had ethical clearance for work on interspecies chimeras. In March, China’s government announced revised rules for ethically problematic research involving human genetics, including requirements for ethics reviews. The mandate came 5 years after a Chinese scientist sparked worldwide outrage by announcing he had helped create genetically edited babies.

////

India has made tests mandatory for cough syrups before they are exported, a government notice showed last Tuesday, after Indian-made cough syrups were linked to the deaths of dozens of children in Gambia and Uzbekistan. https://theprint.in/india/india-makes-tests-mandatory-for-cough-syrup-export-after-overseas-deaths/1589441/

Any cough syrup must have a certificate of analysis issued by a government laboratory before it is exported, effective June 1, the government said in a notice dated May 22 and shared by the health ministry on Tuesday.

India’s $41 billion pharmaceutical industry is one of the biggest in the world but its reputation was shaken after the World Health

Organization (WHO) found toxins in cough syrups made by three Indian companies.

Syrups made by two of these companies were linked to the deaths of 70 children in Gambia and 19 in Uzbekistan last year.

“Cough syrup shall be permitted to be exported subject to the export sample being tested and production of certificate of analysis,” said the notice issued by the trade ministry.

The health ministry did not immediately respond to a query on whether testing would be required for cough syrups sold in the domestic market.

////

In 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged and other effective drugs were elusive, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) emerged as a lifesaving treatment. But now, 3 years later, all the approvals for COVID-19–fighting antibodies have been rescinded in the United States, as mutations of the SARS-CoV-2 virus have left the drugs—which target parts of the original virus—ineffective. https://www.science.org/content/article/covid-19-virus-mutated-outsmart-key-antibody-treatments-better-ones-coming?

Researchers around the globe are now trying to revive antibody treatments by redesigning them to take aim at targets that are less prone to mutation. Just this week, for example, researchers in Canada reported that they’ve created antibody like compounds able to grab dozens of sites on viral proteins at the same time, acting as a sort of molecular Velcro to restrain the virus even if some of the sites have

mutated to elude the drug candidate. Other researchers have taken less radical approaches to producing mutation-resistant antibodies.

All, however, worry that the work may be slow to reach the clinic. With the pandemic emergency declared over in the U.S. and other countries, governments and industry may have less incentive to develop promising new COVID-19 treatments. “There is no business model for this anymore,” says Michael Osterholm, a public health expert at the University of Minnesota.

The antibodies that initially saved lives all glommed on to the tip of spike, the protein SARS-CoV-2 uses to attach to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a receptor on the surface of human cells. For the first 2 years of the pandemic, spike changed modestly enough for the mAbs to continue to work. But as the virus encountered more people with antibodies from previous infections and vaccination, new variants emerged with extensive mutations in the ACE2-binding region, known as the receptor-binding domain (RBD). The variants dodged treatment and left pharma companies scrambling. “By the time you’ve isolated a good [mAb] the virus has moved on,” says Laura Walker, who heads infectious disease biotherapeutics discovery and engineering for Moderna.

Now, researchers are seeking antibodies targeting segments of spike that the virus can’t mutate without losing its ability to infect cells. “People are fishing for that hidden gem that targets something so conserved that the virus cannot mutate away from it,” says Jean-Philippe Julien, an immunologist at the University of Toronto.

In March, for example, an international team led by researchers at the University of Italian Switzerland reported that it had isolated several human antibodies aimed at conserved targets on spike, unchanged across multiple viral variants. One binds to a site known as the fusion peptide, preventing the virus from merging with human cells. In cell-based assays, the antibody bound to four separate families of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2. Another antibody, which targets a spike site known as the stem helix, blocked all SARS-CoV-2 variants from fusing with human cell membranes.

A separate approach takes aim at the human protein, ACE2, that SARS-CoV-2 and its relatives bind to on the cell surface. In mid-May, Bieniasz and his colleagues reported encouraging results in Nature Microbiology. They injected mice with copies of a soluble version of the human ACE2 receptor. Thirty-five days later, they screened the animals’ blood serum for antibodies that targeted ACE2 and blocked SARS-CoV-2 from binding to it. They selected the most potent and injected it into mice that had been infected with a SARS-CoV-2 variant or a variety of other sarbecovirusus, the group of human and animal viruses that includes SARS-CoV-2. The antibody “was equally effective against all of them,” Bieniasz says.

But others are concerned that targeting human proteins could prompt side effects. They worry about interfering with ACE2’s normal function, as it helps regulate blood pressure among other duties. Recent reports have added to the concern by suggesting that people with Long Covid may be producing antibodies against their own proteins, including ACE2.

A third strategy looks to modify the structure of antibodies themselves in hopes of making them more potent. Antibodies are usually Y-shaped, with two arms that can attach to two separate targets. Julien and his colleagues have designed a family of spherical “multibodies,” each with 24 attachment sites. In its most recent study, published this week in Science Translational Medicine, the Toronto team designed two different multibodies, one in which all 24 binding sites targeted the same site on SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein, the other that targeted three different sites. When they injected their multibodies into infected mice, they found that both designs neutralized the virus at doses well below those needed for conventional antibodies. The three-target multibody also neutralized all recent subvariants and a wide array of viruses more distantly related to SARS-CoV-2.

But the momentum needed to turn the new antibodies into approved drugs may be waning. In March, President Joe Biden’s administration launched Project Next Gen to help commercialize vaccines, mAbs, and other therapeutics. But the $5 billion for the effort could soon evaporate, a likely victim of ongoing negotiations between the administration and Congress over the U.S. debt ceiling. With little government help, pharma companies may be loath to pour hundreds of millions of dollars into commercializing new treatments. “It’s going to take long-term investment,” Osterholm says. “That is something we are missing.”