Author CDC/ Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Inger K. Damon, and Sherif R. Zaki

After a meeting behind closed doors, an expert panel of the World Health Organisation (WHO) announced on 25 June that the rapidly growing monkeypox epidemic does not yet warrant the status of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)—a verdict the agency has accepted. (www.science.org/content/article/who-monkeypox-decision-renews-debate-about-global-alarm-system-outbreaks?)

The panel’s conclusion was widely criticized by virologists, epidemiologists, and public health experts, and it has triggered a new debate about the purpose of the PHEIC, an instrument created to help improve the response to international health threats. “I think they made a big mistake,” says Yale School of Public Health epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves, who advised the committee. “They punted.”

WHO has previously come under fire for waiting too long to declare a PHEIC for COVID-19 and Ebola epidemics in West Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The agency’s “track record is that they tend to be on the later side of things,” says Jeremy Youde, a global health researcher at the University of Minnesota, Duluth. “Right now PHEICs send the message that WHO is the last institution to grasp that a newly identified outbreak is indeed a public health emergency of international concern,” adds biologist Michael Worobey of the University of Arizona. “The window may already have closed on stopping the establishment of a new sexually transmitted disease worldwide, but a PHEIC has not even been declared.”

How helpful a PHEIC truly is remains a matter of debate as well. The declaration obligates member countries to follow WHO’s recommendations, such as sharing data on cases, and allows the agency to issue travel advice.

////

As some countries, especially the US, begin a vaccination campaign against monkeypox, concerns rise that the demand may soon far exceed the available supply. (www.nytimes.com/2022/07/01/health/monkeypox-vaccine-bavarian-nordic.html?)

Jynneos, the only vaccine developed for monkeypox, is made by a small Danish company, Bavarian Nordic. The company is expected to send about two million doses to the US by the end of the year, but can produce less than five million more for the rest of the world.

The scope of the monkeypox outbreak is uncertain, said Angela Rasmussen, a research scientist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. But the current supply “is certainly not enough to vaccinate everybody who’s going to be at risk,” she said.

Roughly 60 countries are grappling with monkeypox cases, and all except the US will need to share available doses — enough for fewer than 2.5 million people — until early 2023.

But, already, several countries are vaccinating close contacts of patients and anyone else at high risk — an approach that may rapidly ratchet up the number of doses required worldwide.

If the number of cases continues to rise unchecked, warns Zain Rizvi, who studies access to medicines at the advocacy group Public Citizen, monkeypox may become permanently entrenched in several countries, leading to outbreaks for years to come.

The global count has risen to about 5,500 cases, and at least another 5,000 are under investigation. Cases in Europe have tripled in the last two weeks, according to the WHO. The US has identified 400 monkeypox cases, but the real number is believed to be much higher.

The US stockpile holds about 56,000 doses that will be distributed immediately, and federal officials expect to receive another 300,000 doses in the next few weeks. An additional 1.1 million doses have been manufactured for the US.

Bavarian Nordic is talking to other manufacturers that could produce more doses, but that, too, generally takes at least four to six months, Chaplin said.

There is an alternative: ACAM2000, a version of the vaccine used to eradicate smallpox decades ago, which is also likely to be effective against monkeypox. But that vaccine has harsh side effects, including heart problems, and can be fatal in people with certain conditions.

“I want to underscore the absurdity of relying on one single manufacturer to be the global supplier for a vaccine that is needed to curb outbreaks,” Rizvi said. “It’s so stupid that we’re back in this situation.”

But there is a strategy that could double the number of people who can be vaccinated: use a single shot instead of the recommended two. (www.science.org/content/article/there-s-shortage-monkeypox-vaccine-could-one-dose-instead-two-suffice?)

Compelling data from monkey and human studies suggest a single dose of the vaccine solidly protects against monkeypox, and that the second dose mainly serves to extend the durability of protection.

The United Kingdom, Germany, and Canada are offering the vaccine to anyone deemed at high risk of infection—for now that’s primarily men who have sex with men (MSM) who have multiple partners. The United States at first limited the vaccine to contacts of confirmed cases, including health care workers, but on 28 June also began to offer it to people at high risk of infection who had presumed exposures, which includes MSM “in an area where monkeypox is spreading.”

The United Kingdom is already giving people just one shot for now, advising them that they might want the second dose if they have an ongoing risk.

Bavarian Nordic CEO Paul Chaplin, an immunologist, also embraces the single dose plan. Studies have shown that immune responses triggered by a single shot of the MVA vaccine declines after 2 years, which is why the approved vaccine schedule calls for a second shot. But Chaplin says immune memory is so robust after a single dose that a booster given 2 years later leads to the same immune response as the standard schedule. If countries decide to use single shots now, they have a long time to add the booster.

///

The origins of the latest monkeypox outbreak outside of Africa are now becoming clearer. Genetic analysis suggests that although the monkeypox virus is rapidly spreading in the open, it has been silently circulating among people for years. www.nytimes.com/2022/06/23/health/monkeypox-origin-mutations.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article

Health officials have already identified two versions of monkeypox among American patients, suggesting at least two separate chains of transmission. Researchers in several countries have found cases with no known source of infection, indicating undetected community spread. And one research team argued last month that monkeypox had already crossed a threshold into sustainable person-to-person transmission.

The genetic information available so far indicated that, at some point in the last few years, the virus became better at spreading between people, said Trevor Bedford, an evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre in Seattle. “Genomic patterns would suggest this occurred around 2018,” he added.

If the virus has adapted to include people as hosts, monkeypox outbreaks could become more frequent and more difficult to contain. That carries the risk that monkeypox could spill over from infected people into animals — most likely rodents — in countries outside Africa, which has struggled with that problem for decades. The virus may persist in infected animals, sporadically triggering new infections in people.

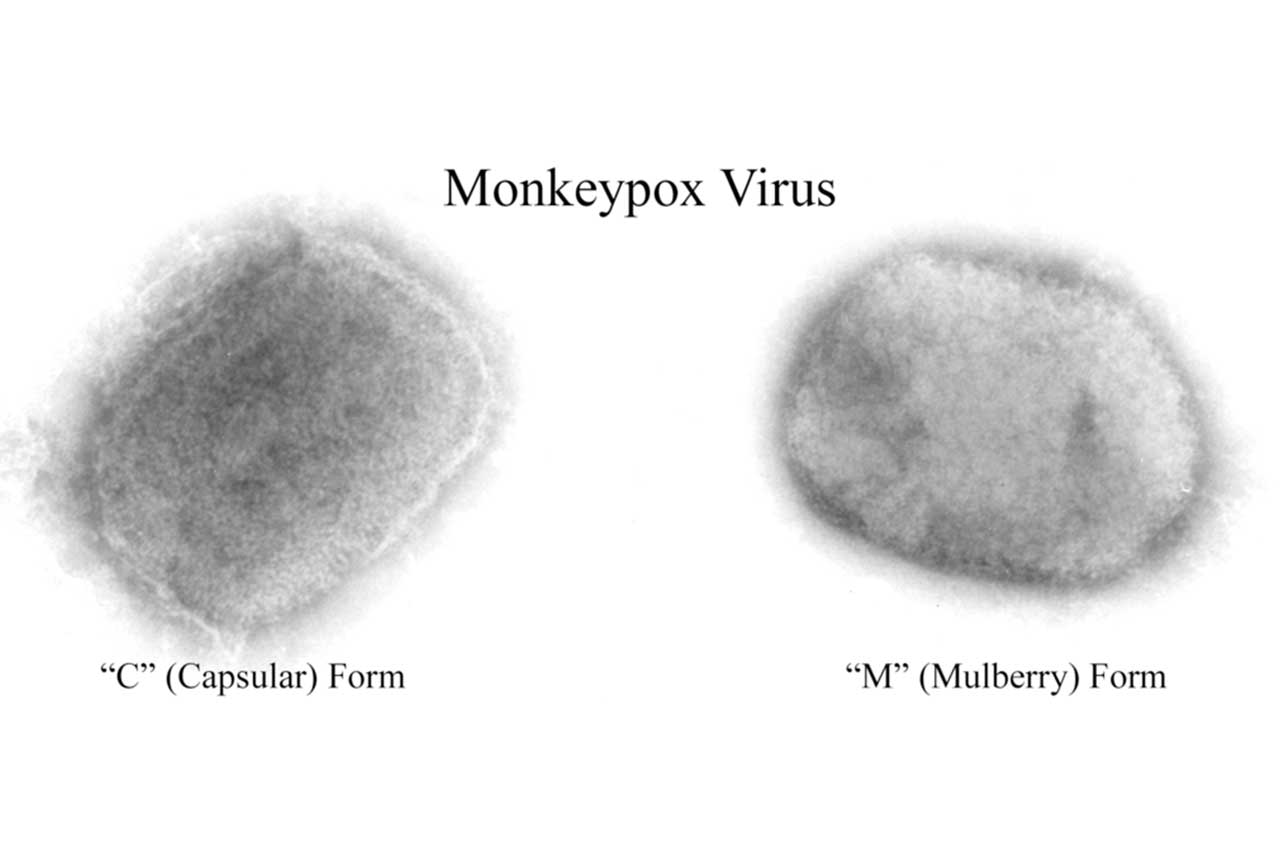

Monkeypox is a large double-stranded DNA virus, about seven times as large as the coronavirus. DNA-based viruses can correct their own errors when they replicate their genetic material. They may collect just one or two mutations per year compared with 20 to 30 mutations for an RNA virus like the coronavirus.

But the monkeypox virus seems to have amassed an unexpectedly high number of mutations — nearly 50 compared to a version that circulated in 2018, according to preliminary analyses.

Some experts have cautioned for years that the eradication of smallpox in 1980 left the world vulnerable to the broader family of poxviruses and raised the odds of monkeypox evolving into a successful human pathogen.

////

Globally, the number of weekly COVID-19 cases has increased for the third consecutive week, after a declining trend since the last peak in March 2022. During the week of 20 to 26 June 2022, over 4.1 million new cases were reported, an 18% increase as compared to the previous week. The number of new weekly deaths remained similar to that of the previous week, with over 8500 fatalities reported. (reliefweb.int/report/world/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-weekly-epidemiological-update-29-june-2022)

These infections will also inevitably add to the toll of long COVID cases. According to ONS data, the supposedly “mild” waves of Omicron during 2022 have brought more than 619,000 new long COVID cases into the clinical caseload, promising an enduring and miserable legacy from this latest phase, Danny Altmann professor of immunology at Imperial College London writes in The Guardian newspaper (www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/jul/01/herd-immunity-covid-virus-vaccine?)

Rather than a wall of immunity arising from vaccinations and previous infections, we are seeing wave after wave of new cases and a rapidly growing burden of long-term disease. What’s going on? The latest scientific research has some answers.

During May and June two new variants, BA.4 and BA.5, progressively displaced the previous Omicron subvariant, BA.2. They are even more transmissible and more immune-evasive. Last week a group of collaborators, including me (Altman) and a professor of immunology and respiratory medicine, Rosemary Boyton, published a paper in Science, looking comprehensively at immunity to the Omicron family, both in triple-vaccinated people and also in those who then suffered breakthrough infections during the Omicron wave. This lets us examine whether Omicron was, as some hoped, a benign natural booster of our COVID immunity. It turns out that isn’t the case.

Most people – even when triple-vaccinated – had 20 times less neutralising antibody response against Omicron than against the initial “Wuhan” strain. Importantly, Omicron infection was a poor booster of immunity to further Omicron infections.

Contrary to the myth that we are sliding into a comfortable evolutionary relationship with a common-cold-like, friendly virus, this is more like being trapped on a rollercoaster in a horror film. There’s nothing cold-like or friendly about a large part of the workforce needing significant absences from work, feeling awful and sometimes getting reinfected over and over again, just weeks apart. And that’s before the risk of long COVID. While we now know that the risk of long COVID is somewhat reduced in those who become infected after vaccination, and also less in those from the Omicron than the Delta wave, the absolute numbers are nevertheless worrying.

The first generation of vaccines served brilliantly to dig us out of the hole of the first year, but the arms race of boosters versus new variants is no longer going well for us.

A study reported in the BMJ last week showed us that the protection gained from a fourth booster dose likely wanes even faster than previous boosters. This leaves us between a rock and a hard place: continue to offer suboptimal boosters to a population who seem to have lost faith or interest in taking them up, or do nothing and cross our fingers that residual immunity might somehow keep a lid on hospitalisations (as happened in South Africa and Portugal).

/////

Lalita Panicker is Consulting Editor, Views and Editor, Insight, Hindustan Times, New Delhi