Article by Lalita Panicker, Consulting Editor, Views and Editor, Insight, Hindustan Times, New Delhi

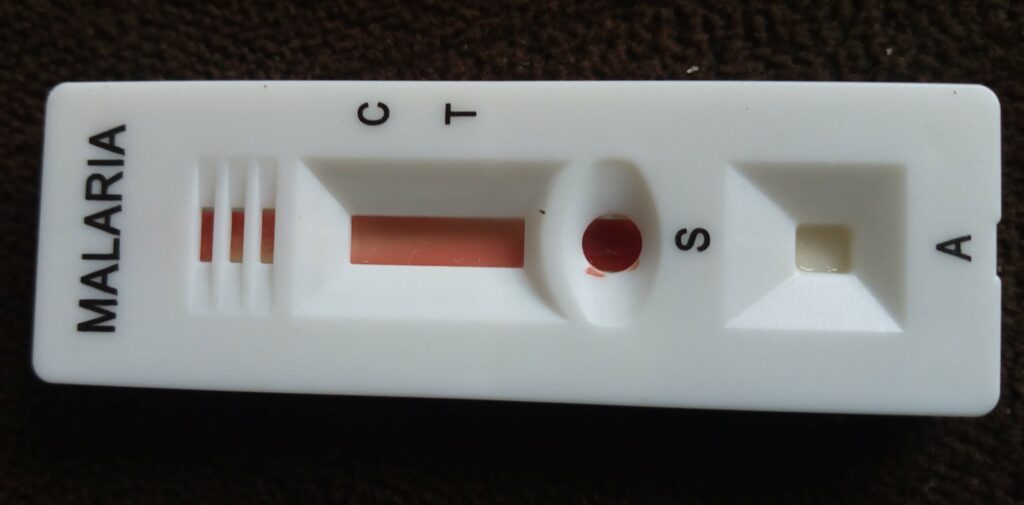

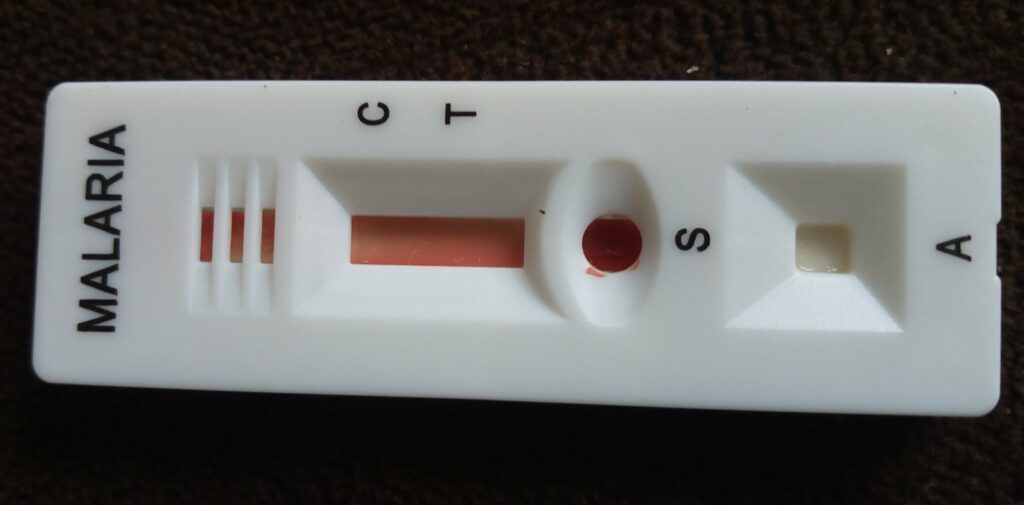

After a 60-year quest, childhood malaria vaccinations were administered to infants and toddlers in Cameroon on 22 January, the world’s first routine immunization against the disease. Remarkably, the RTS,S or Mosquirix, made by GlaxoSmithKline and approved for general use in 2021 by the World Health Organization (WHO) reduces all kinds of deaths among children – not just malaria deaths– by 13%.

The 13% statistic came from a successful WHO pilot campaign in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, where over two million children from age 5 months to 2 years have received the malaria vaccine since 2019. The vaccine prevented about 39% of malaria cases and 32% of severe cases in Phase 3 trials, as compiled by WHO.

Nineteen other African countries aim to begin administering RTS,S or another recently approved malaria vaccine, R21, routinely this year. Both are given as a series of four shots, normally beginning in the sixth month of life. Malaria kills about 470,000 children younger than age 5 in Africa annually. In Cameroon, malaria incidence grew by 49% between 2015 and 2022.

“While 39% efficacy seems low for a vaccine, when we consider the sheer burden of malaria, this means potentially a huge reduction in cases and deaths among children,” said Dr Aaron Samuels, CDC’s Kenya malaria program director, in 2021. In 2022, there were an estimated 249 million cases of this mosquito-borne disease globally and 600,000 deaths. Africa was home to 95% of these deaths, including almost half a million children under 5.

The new vaccine does present some challenges: children need four doses over a year to be fully vaccinated, which may be difficult to coordinate outside of clinical trial settings. A huge quantity will be needed, and each dose costs about $9.80. There had been concerns about getting an adequate supply from pharma company GSK. But the approval of a second malaria vaccine by WHO, called R21/Matrix-M, should help address shortages since it requires only 3 doses, each costing $2-4, with 100 million doses expected to be available later this year.

The vaccine campaign began last Monday in Cameroon, with the goal of reaching 6.6 million children across 20 African countries by 2025. Dr Kate O’Brien, director of the Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals at WHO, expects the scale-up of the malaria vaccine will save tens of thousands of lives annually.

Certainly, some of these averted deaths will be directly related to malaria. But the unexpected development is that the vaccine seems to reduce deaths where malaria is only a contributing factor, exacerbating other diseases but not killing the patient itself, according to Dr Steve Taylor, a global health and infectious disease expert at Duke.

As an example, he notes that contracting malaria makes you more likely to get salmonella disease – the most common bloodstream infection in Africa with a case fatality of up to 20-25%. Malaria also seems to make people susceptible to bacterial infections more broadly, with a Lancet study out of Eastern Kenya in 2011 demonstrating that over half of bacteraemia cases were attributable to malaria.

In an email to NPR, Dr Mary Hamel, WHO’s senior technical officer on malaria, also describes how children who have HIV or face chronic malnutrition are at higher risk of severe malaria, which, in turn, can exacerbate HIV and malnutrition, potentially leading to death. “We have seen this before with malaria,” she says, in trials where children got insecticide-treated nets or preventive antimalarial tablets, “that the reduction in mortality is more than what one would expect from a decrease in malaria deaths alone.”

So, while malaria experts are celebrating the vaccine, it needs to be part of a preventive program with mosquito nets and other existing tools, said Dorothy Achu, lead for tropical and vector-borne diseases in the WHO Regional Office for Africa, at the press conference. “In the malaria community, we always say we do not have any magic bullet.”

While the vaccine itself may only prevent 30-40% of malaria cases, this number rises to 90% when combined with mosquito nets and protective malarial tablets, according to a Lancet Infectious Diseases study from 2023.

///

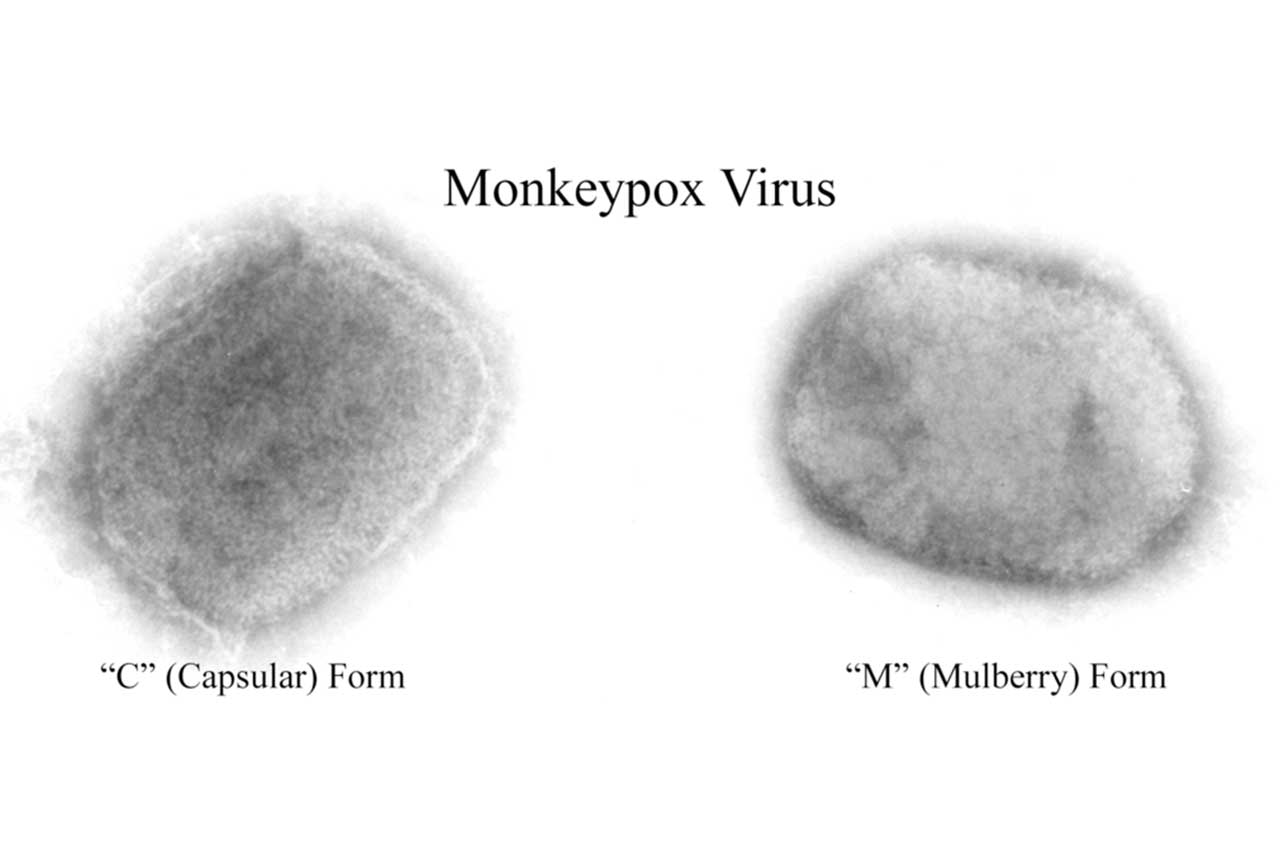

It had been over 30 years since the last case of diphtheria was seen in Guinea. So when patients began showing up six months ago with what looked like flu symptoms — fever, cough and sore throat – doctors weren’t alarmed. Until the children started dying.

That’s when they realized that this long-time scourge, long quashed by vaccination, was back. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2024/01/23/1226155791/why-diphtheria-is-making-a-comeback?

As of December 2023, there have been around 25,000 cases of diphtheria in West Africa and 800 deaths. In Guinea, the cases were clustered in Siguiri, a rural prefecture in the country’s northeast, and early data showed that 90% occurred in children under the age of 5.

Diphtheria is a highly contagious bacterial infection spread through direct contact with infected sores or ulcers but primarily through breathing in respiratory droplets. The bacteria then releases toxins, causing inflammation that blocks the airways; a thick mucus-like substance (called a “pseudo membrane”) can form at the back of the throat.

“This can kill by suffocating the patient,” says Adélard Shyaka, medical coordinator for Doctors Without Borders in Guinea. “But also the toxin moves through the body and can damage the heart, the kidneys, the nervous system.” Such damage — via suffocation, myocarditis, kidney failure and nerve malfunctioning — means diphtheria is fatal in up to 50% of cases without treatment.

The disease, which was a global scourge for much of the 20th century, is also almost entirely preventable through vaccination. After the diphtheria inoculation was included on the World Health Organization’s essential vaccine list in the 1970s, cases decreased dramatically worldwide. “Now, it’s an almost forgotten disease,” says Shyaka.

Guinea was particularly vulnerable because of its low diphtheria vaccination rate – only 47% in 2022, with the hardest-hit Siguiri prefecture having even lower coverage at 36%. COVID-19 disrupted routine vaccination campaigns in West Africa and was associated with an uptick in vaccine mistrust. But for diphtheria and other preventable childhood illnesses, the immunization problem predated the pandemic due to supply chain difficulties, insufficient funding, and complacency, among other reasons, leaving the region vulnerable to a cluster of cases swelling into an outbreak.

In Guinea, Doctors Without Borders says its staff has supported local health workers in addressing diphtheria. Together, they’ve reduced mortality at Siguiri’s Centre for the Treatment of Epidemics from 38% to 5% over the past few months. Patients with mild symptoms are sent home with antibiotics, while more severe cases are admitted to the hospital and treated with an antitoxin, as appropriate.

However, shortages of both vaccines and antitoxins continue to hamper a full-scale response to the diphtheria outbreak, according to Louise Ivers, an infectious disease physician and the director of the Harvard Global Health Institute. Presently, only two or three companies make the antitoxin, and each batch of 1,500 doses takes about four weeks to prepare, harvested from horse blood. “Nobody wants to make it,” says Ivers, because of how rarely this antitoxin is usually needed – there were fewer than 9,000 cases globally in 2021 – and how impoverished communities facing diphtheria tend to be.

The only sure way this outbreak ends is through vaccination, suggests Ivers, who has first-hand experience responding to diphtheria in Haiti between 2003 and 2012. However, similar market dynamics may help explain the global shortage of diphtheria vaccines. “If we can catch back up with DPT [vaccines] and diphtheria boosters and get our communities highly vaccinated,” she says, “then we can prevent outbreaks.”

////

In late December 2023, Brazil’s National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) suspended the commercialization of approximately 1200 hair creams because of reports of eye irritation and temporary blindness. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/hair-creams-do-you-know-health-risks-2024a10001ni?ecd=mkm_ret_240127_mscpmrk-OUS_IntStories_etid6260491&uac=398271FG&impID=6260491

A similar measure encompassing all hair creams sold in the country had already been announced by the agency in March. However, after a few weeks, ANVISA issued a resolution with rules for the products’ commercialization, allowing them back on the shelves.

With the new resolution, the sale of products that do not comply with the standards has once again been suspended. The reason is that reports of adverse events have re-emerged. These events include temporary vision loss, headaches, and burning, tearing, itching, redness, and swelling of the eyes. According to reports, these adverse effects occurred mainly in people who used the specific products before swimming in the sea or in pools, or even going out in the rain.

The banned products contain 20% or more ethoxylated alcohols in their formulations. Products containing methylchloroisothiazolinone and methylisothiazolinone were already prohibited. These substances, used as preservatives, are considered toxic to the skin and mucous membranes, potentially causing allergies and burns to the eyes and skin. They also have a high pulmonary and neurological toxicity. All these substances are eye irritants and can cause chemical keratitis. In extreme cases, corneal ulcers may develop, leading to vision loss.

The Brazilian Council of Ophthalmology also issued a warning on these products. It emphasized that, in addition to the sales prohibition, consumers should check the labels of hair creams to make sure that these toxic substances are not present in the product formulation.

The ANVISA website contains a list of creams that are considered safe and have not had their commercialization suspended, along with links to adverse event notifications reported by healthcare professionals or consumers.

////

The Serum Institute of India (SII) will join a growing CEPI network of vaccine producers in the Global South to support more rapid, agile, and equitable responses to future disease outbreaks. CEPI — Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations — is an innovative global partnership working to accelerate the development of vaccines and other biologic countermeasures against epidemic and pandemic threats. www.thehindu.com/business/Industry/serum-institute-of-india-joins-global-network-to-boost-production-of-affordable-outbreak-vaccines/article67769714.ece

CEPI has articulated an aspirational goal: vaccines should be ready for initial authorisation and manufacturing at scale within 100 days of recognition of a pandemic pathogen, when appropriate. The addition of SII to the CEPI manufacturing network will be a significant boost to vaccine production efforts in Global South regions, and take it a step closer to achieving the 100 Days Mission.

The idea is to combine the process of delivering a vaccine within 100 days with improved surveillance providing earlier detection and warning, and swift use of interventions such as testing, contact tracing and social distancing to suppress disease transmission. According to CEPI, this would give the world a better chance of containing and controlling future pathogenic threats and averting the type of catastrophic global public health and socio-economic impacts caused by COVID-19.

The manufacturing network will focus on vaccine makers in the Global South near areas at high risk of outbreaks caused by deadly viral threats like Lassa Fever, Nipah, Disease X, and other pathogens with epidemic or pandemic potential prioritised by CEPI. The Global South broadly comprises Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia (excluding Israel, Japan, and South Korea), and Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand).

To prepare for such a scenario, CEPI is investing up to $30 million to build upon SII’s proven track record of rapid response to outbreaks of infectious diseases, expanding the company’s existing ability to swiftly supply investigational vaccines in the face of epidemic and pandemic threats, according to a press release. This would then enable CEPI-backed vaccine developers to quickly transfer their technology to their partners within days or weeks of an outbreak to begin rapid production and equitable distribution of affordable vaccines to affected populations.