In a packed San Francisco conference room last Tuesday, upbeat company representatives and scientists presented detailed clinical trial data on the first Alzheimer’s treatment shown to clearly, albeit modestly, slow the disease’s normal cognitive decline. The antibody therapy has buoyed a field marked by decades of failures. Now, it appears to be on the cusp of being greenlit by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). www.science.org/content/article/hail-new-antibody-treatment-alzheimers-safety-benefit-questions-persist?

Yet other researchers warn of potential risks, including brain swelling and brain haemorrhages that were linked to the recently disclosed deaths of two trial participants who received the antibody. Officials from the lead company sponsor, Eisai Co., confirmed the two deaths but denied that they resulted from its experimental therapy.

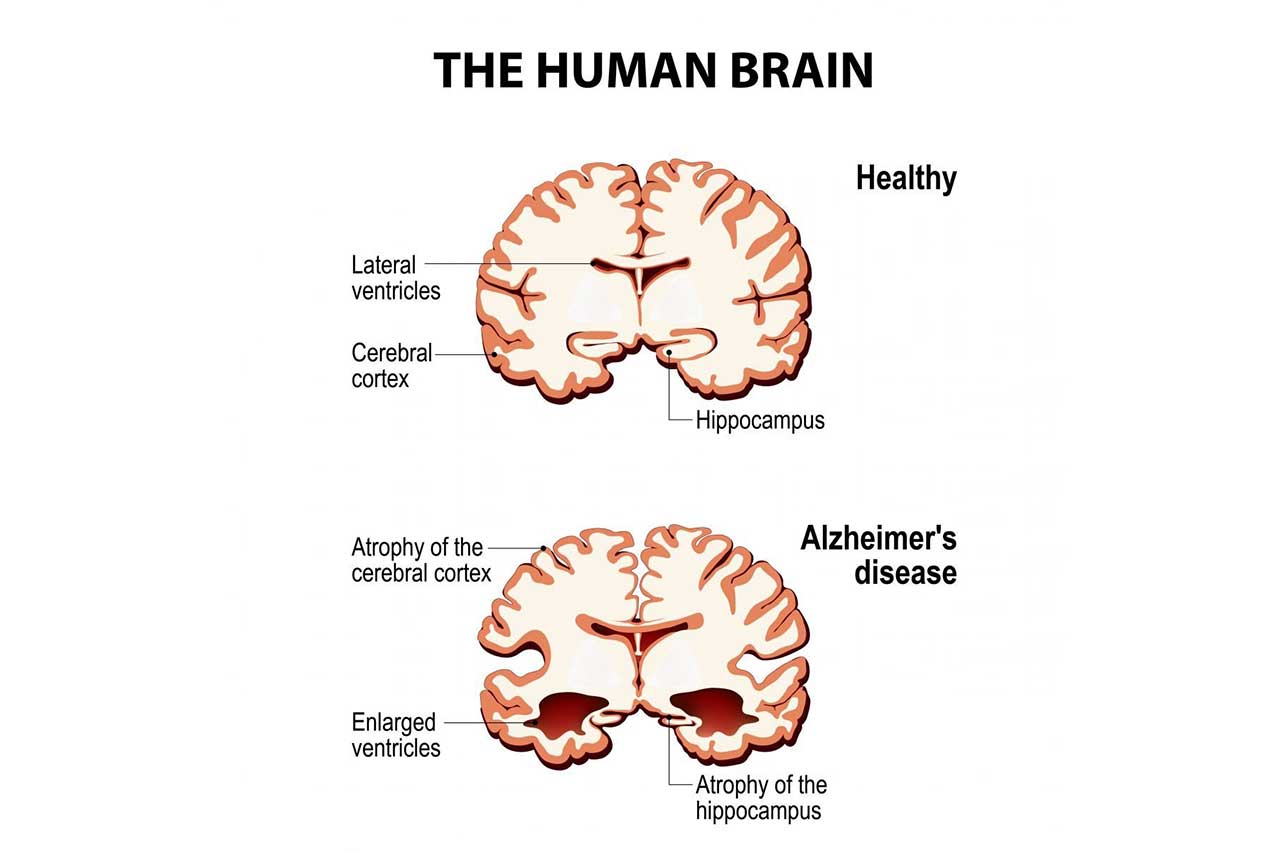

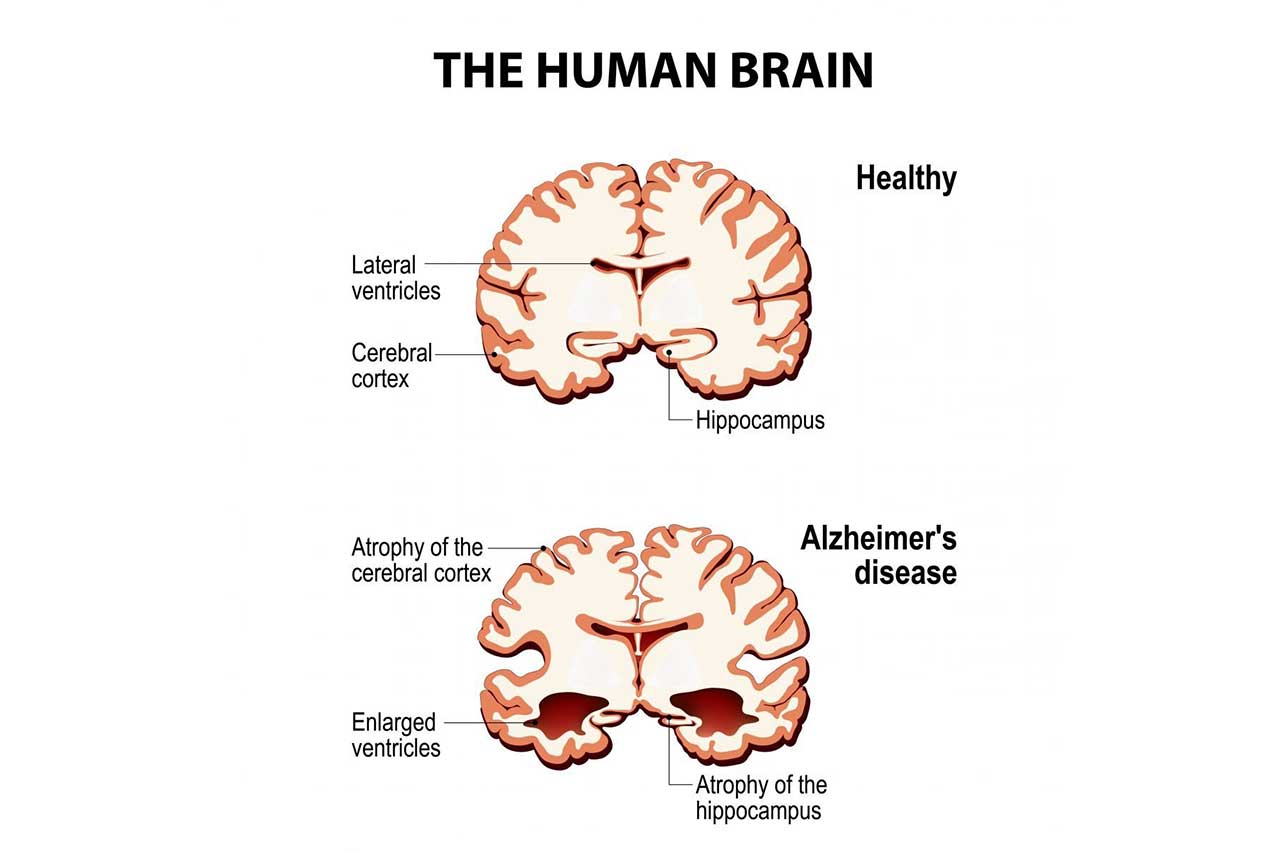

The Japanese company has been developing the monoclonal antibody lecanemab to remove a protein called amyloid-beta in early-stage Alzheimer’s. The protein clusters in the brains of people with the disease and is widely thought to cause its neuro-degeneration. Other antibodies and strategies have chased amyloid’s removal, but lecanemab is the first to do so and clearly delay the onset of dementia symptoms. Many scientists and advocates are hailing these results as the strongest validation yet of the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s.

The new data “confirms this treatment can meaningfully change the course of the disease for people in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s,” the Alzheimer’s Association said in a statement.

In a series of presentations late Tuesday at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease Conference, along with a paper simultaneously released in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), Eisai, its partner Biogen and several researchers followed up on a September press release that had briefly detailed the results of the pivotal lecanemab trial, which included 1,795 early-stage Alzheimer’s patients. Last Tuesday’s talks and paper confirmed the earlier announcement that lecanemab, which was given by intravenous infusion every other week, slowed the rate of cognitive decline by 27% in people taking it for 18 months, compared with similar participants on a placebo.

“Longer trials are warranted,” said the director of the Alzheimer’s Research unit at Yale University and a leader of the study, Christopher van Dyck. The 18-month study ended in March of 2021, and since then patients have been offered the chance to participate in an “extension” trial in which they can all receive infusions of lecanemab every other week if they wish.